The Mystery of Montmartre

By William Le Queux

St. Louis Post-Dispatch: St. Louis, MO. December 23, 1900 – Section A, page 101

Christmas! Chrsitmas [sic] here again. Mention of the feast stirs my memory and causes me certain twinges of conscience.

In those days I was one of a crowd of reckless law students who lived high up in those dingy houses in the Rue Cassette.2 Three of us lived together in those rickety dirt-begrimed rooms on the fifth floor in the Rue Cassette—No. 11, to be exact. The names of my companions were Fremont and Duqusne [sic].

The Rue Cassette in Paris (photo by Wikimedia user Chabe01)

This record of adventure, however, mainly concerns another. That other was Pierrette,3 the dark-eyed, neat-ankled modiste employed at Carlier’s atelier in the Rue-de-la-Paix.

Every man who wore the black velvet cap of the “Verveau de Paris”4 knew Pierrette, and all treated her with respect, for she never went to the Lorraine or places of that stamp, and in her room over the Rue Lepic lived her younger sister, who was a confirmed invalid. Pierette [sic] supported her upon her slender earnings.

Pierrette was exuberant of spirit, chic in dress, however cheap its material: tall, with a figure supple and graceful, and with dark hair. All three of us were in love with her, but myself she favored most of all.

Ah! in those days when all of us believed that we should one day make France ring with our declarations, Pierrette and I built castles in the air while in the Luxembourg Gardens or in the Bois we walked hand in hand, happy in each other’s love. Beneath her bodice she wore, suspended round her neck, the tiny gold crucifix which I had given her.

The examination list was issued on Christmas eve, and therein, to my unbounded joy, I found my name as having passed my third year in equity. That night Fremont and Duquesne gave a punch in my honor, and among the fellow-students was their favorite, my own Pierrette. We broke up about 8 o’clock on Christmas morning, and on going forth into the street found that snow had been falling heavily, but had now ceased, and the moon was shining. Pierrette bade farewel [sic] to my companions, and then we trudged through the sonw [sic] toward her home.

“I wish, Paul, you would let me go home alone,” she said, suddenly, as we were passing the Jardin du Luxembourg.

“Why? You’ve never wished to go alone before.”

“No,” she replied firmly; “but I wish you to return now. I have a reason.”

“What is it?” I demanded.

She hesitated, then answered in a hard, strained voice:

“I cannot tell you, Paul.”

“The boulevard is not safe for a girl alone at this hour,” I said, decisivey [sic]. “You must allow me to go with you. Come.” and taking her arm I walked forward.

“No!” she cried, drawing back. “I will not allow you to—to run such a risk!”

“Risk? What do you mean?” I laughed. “It is surely you yourself who would run a risk by walking alone.”

She would, however, hear no argument. It seemed that with that spirit of perversity which sometimes seizes the capricious sex she had firmly resolved to go home alone.

“Come, wish me au revoir, Paul, and let me go,” she urged. “Tomorrow is the fete of Noel. We meet at 10, remember.”

And snatching my hand, she raised it to her lips and hurried away.

I stood by the railings gazing after her in surprise. Soon she was lost to sight, but had left her shapely footsteps in the snow. Of a sudden a thought flashed through my mind. Was it possible that, during the evening when she had been chattering with my fellow students, she had made an appointment to meet one of them? This idea became firmly fixed in my mind. Pierrette, whom I loved with all the strength of my being, was false to me!

I stood there rigid, unable to make up my mind whether to follow her or to turn back home and wait her explanation on the morrow.

In the snow were prints of the feet of two persons going in the same direction—one of those of a man who had passed a short time previously, the others of Pierrette. She had spoken of a risk, and I think that it was my curiosity which prompted me to follow those footprints.

I cannot tell what streets I traversed, except that the footprints led me along the Rue de Medicis and the Boulevard Michel, across the river, along the Rue Montmartre, and then through that maze of narrow, crooked streets behind the Boulevard de Clinchy.5

The fact that my love had exactly followed the steps of the wanderer struck me as more than curious. Further, the footsteps of the wanderer were strange, inasmuch as one print was large and heavy, the other small and round. I concluded that the fellow had a wooden leg.

At length, after following the trail half and hour or more, it turned into a dark entry of a narrow, squalid, unfamiliar street and led across an open courtyard to a half open door. I went forward and along a creaking passage which led out at right angles.

Of a sudden I discerned a light shining from within a room, the door of which had been left ajar. Noiselessly I crept up and peered in.

The sight which met my eyes was so startling that I held my breath.

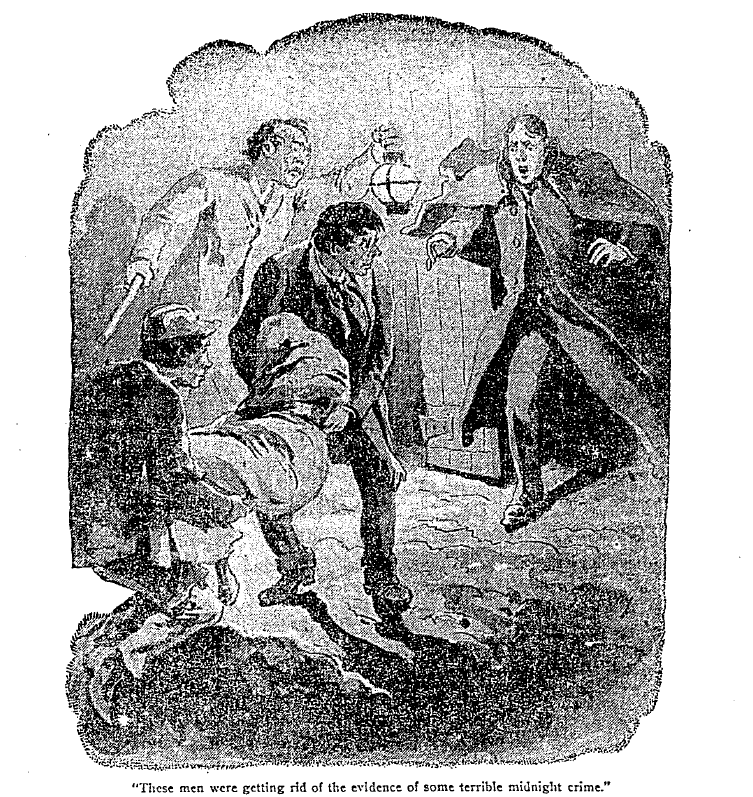

The room was a large one, flagged with stones. On the latter had been taken up and revealed an open grave. Four evil-looking ruffians were there, while upon the floor, wrapped in coarse sacking, lay a body ready for interment. Two smoking lamps threw their uncertain light upon the scene. These men were getting rid of the evidence of some terrible midnight crime! As I watched, one of the ruffians, a fellow in the peaked cap of the Montmartre, emptied a sackful of quicklime into the grave, and then all four raised the body and carried it forward.

Illustration from William Le Queux, “The Mystery of Montmartre,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Beneath the sacking I fancied I detected a movement, and of a sudden a hand was thrust forth.

It was a woman’s hand, slim and white. By the sleeve of gray silk I knew that it was the hand of my love, Pierrette.

“Hold her firmly, Fourneau!6” cried a shock-headed fellow in the slang of the quartier. “Come, fling in the linge (girl) and let us close it down! We’ve been far too long over this tulle (dangerous affair)!”

There burst from my lips a cry which betrayed my presence, and seeing this, I flung myself between the woman I loved and her enemies. Ere the latter were aware of it I had torn the sacking from her, revealing her half clad, stark and dead, with some strange white powder smeared about her face. The next second I received form behind a crushing blow which felled me to the ground.

Of what occurred immediately afterward I have not the slightest idea. The heavy blow upon my skull—struck, I believe, with the spade used in digging the grave—blotted out all consciousness.

My next recollection was of excruciating pains in my head. I opened my eyes, but all was gray and indistinct. For a long time I lay cold, cramped and confined until at last I gained sufficient strength to turn myself and glance aside. The sight that met my eyes held me petrified. Lying close to me was a human head, severed from the trunk—a ghastly object that caused me to start in horror.

But worse! That ghastly, severed head, white and bloodless, with its staring, wide-open eyes and pale gray lips, was that of Pierrette.

I stretched forth my hand and touched it. The cheek was hard and cold.

The mystery of it was inscrutable. Pierrette, whom I loved better than life, had lied to me to enter that fatal trap. She who had been the life and soul of our students’ carousal was now dead and her body dismembered. I rounsed [sic] myself and sat, dumfounded [sic], glaring at the hideous evidence of the tragedy.

Who were those men whom I had surprised? Why had they any motive in taking the life of a poor, hard-working girl? Surely, not to conceal a theft, for poor Pierrette never had in her pocket any greater sum than 5 francs. And the strange white powder upon her face! Why had it been placed there? She had deliberately gone to that place and had openly told me of the risk I should run were I to accompany her. Her own actions had been as mysterious as their tragic outcome.

The place in which I found myself was a square chamber, dark save for a ray of light which, struggling through an air-brick at the further end fell across the pale, dead countenance. There was an odor of damp mouldiness which told me that it was beneath the earth, while the scuttling of rats showed me that I had plenty of companions.

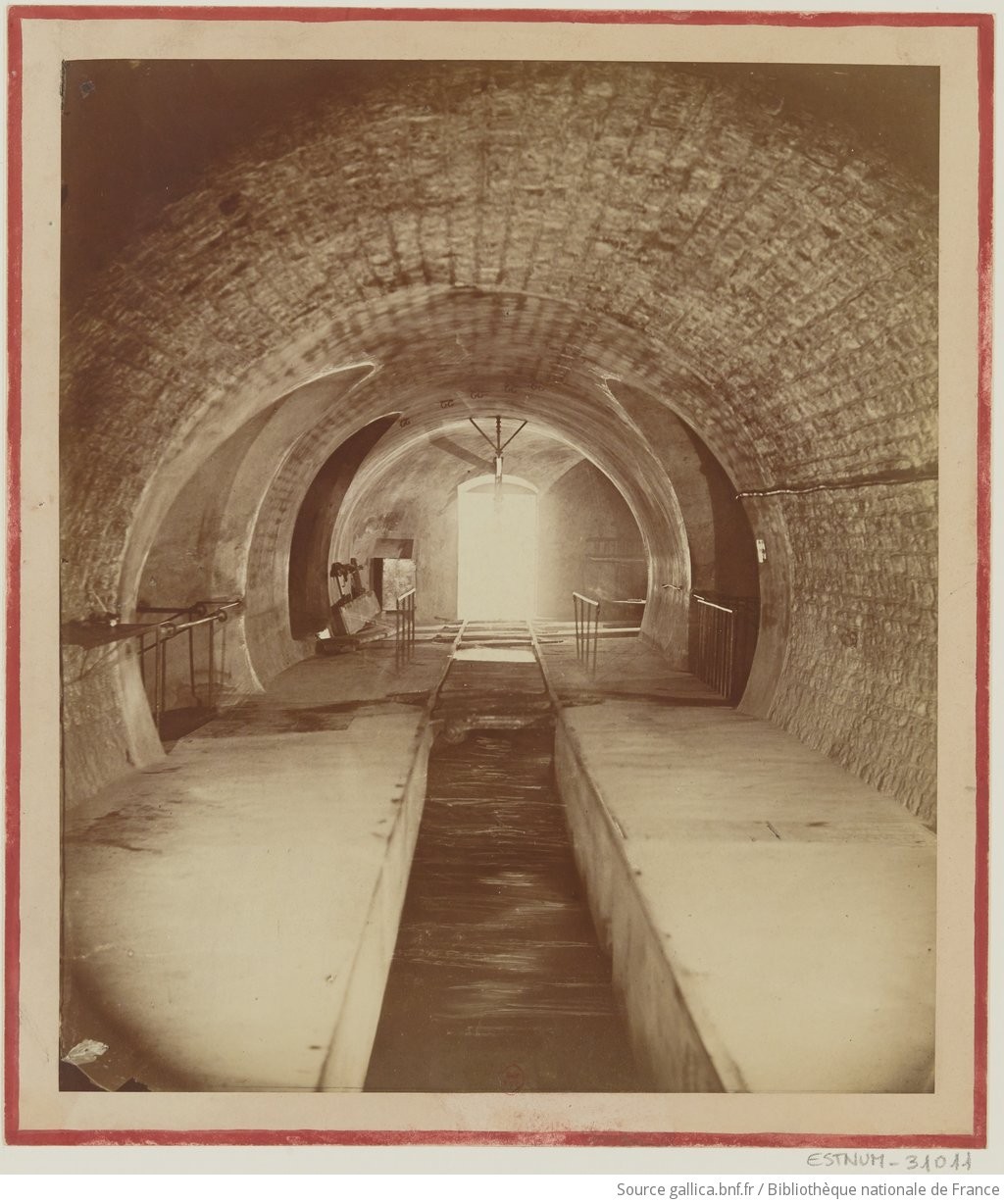

I scrambled to my feet, but so low was that end of the arched cellar that I could not stand upright. Around the walls I searched to find some egress, but there was no door. The only opening, save the air-brick in the wall, was a barred iron grating about three feet square close to the slimy floor. I tried to wrench it out, but it was too securely clamped in the stonework. Whither that opening led I knew not. My examination, however, proved that it could be lifted from the chamber above and that there was a round hole in the roof closed by an iron plate. There were evidences, by the mud, that the chamber could be flooded and that the grating could be opened like a sluice.

I had been caught like a rat in a trap. At any moment my captors could drown me and allow my body to be carried away down that dark tunnel to the sewers of the Seine.

I listened. Yes: the sound I heard was the low lapping of water upon the will. Then I guessed the truth. I was imprisoned in one of the flushing chambers of the sewers. A touch of that rusted iron lever from above and I would be swept into eternity.

The Paris sewers (photo by Félix Nadar, Égouts Paris France, éclusée n°2, ca. 1864-5, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Moments passed, each seeming a full hour. To devise some means of escape racked my brain. And all the time lying there in full view was the ghastly head of my murdered love.

I thought I heard her voice, as though faintly articulated words came from that dead mouth besmirched by the foul mud with which the floor of my tomb was covered. But alas! It was only a dream—that vagary of imagination that is always precursory of madness. Frantic in my efforts to escape, I kissed those cold, hard, unresponsive lips, then beat my hands upon the slimy walls. To life the iron grille would avail me nothing, but my attention turned to that single perforated brick through the holes of which came air and the gray light of day. The perforations made it weak, therefore I endeavored to break it out.

Through the small hole I made I could see that it was still daylight, and that snow still lay upon the ground. There seemed a wall about six feet away, and against that the snow had drifted.

Some half hour later, while I was working noiselessly for dear life, gradually making a hole in which to use the iron bar I had broken down from the grille as a lever to force out the brickwork, I heard a harsh noise behind me. Startled, I turned and saw the grille before the dark culvert slowly rising, grating horribly, but lifted gradually into the roof of the chamber.

During the seconds which elapsed I lived a lifetime.

Of a sudden there was again a loud grating of rusted iron and part of the floor of the chamber fell away, disclosing a dark abyss. There was a terrible stench, a loud crackling and rumbling of waters beneath, then the black tide rose, filling the great hole and gradually flooding the place.

It was as I had anticipated. My captors intended to get rid of me, but ice in the sewer had blocked its passage and the water did not rush through at once, as no doubt it usually did, rising to within a few inches of the airbrick.

I turned my attention again to those loosened bricks, standing up to my waist in the turbid flood and striving desperately to save my life. At last, just when the water had reached my armpits, I succeeded in forcing out a portion of the masonry, making a hole through which I squeezed forth into the outer air.

I found myself in a courtyard surrounded by high walls. Darkness had fallen. I knew that it was Christmas evening and that I had existed in that noisome sewer chamber for many hours. Through the door of an adjoining house I crept noiselessly, fearing lest my enemies were there, and quickly gained the street. Hurrying along through several narrow turnings, I emerged into the Place Pigalle and there informed a policeman of what had occurred.

He noticed the muddy state of my clothes and told me that I had been drinking. I repeated my story, but the fellow would not believe me. So I went to the chief police officer of the arrondisement, but I saw by the manner of the officer who interrogated me that my story was discredited.

However, he sent a detective with me, and we set forth to investigate. Although it was early, the facades of the cabarets where the Montmartrois singers chant their audacious songs were already illuminated. But the arms of the “red windmill” had not yet begun to swing, the Abbaye de Theleme7 had not awakened to life. The Montmartre had not yet shaken off the mock respectability which it assumes by day. Arrived at the Rue Fontaine, we took the first of the narrow streets on the left behind the Boulevard de Clichy when the bewildering truth flashed upon me.

In my hurry to inform the police I had taken no notice of the house from which I emerged.

The detective laughed when he witnessed my perplexity.

“Come,” he said, “you’ve dropped off to sleep in the gutter somewhere and imagined it all. Tell me the truth now.”

“I have not!” I cried angrily. “I tell you that a woman—the woman I loved—has been foully murdered and her body interred secretly here in one of these houses.”

“But which?”

I was compelled to admit that I did not know.

My anxiety to escape and inform the police had caused me to rush forth into the unfamiliar street and then, not knowing the direction of the boulevard, I had taken one turn after another before coming to the Place Pigalle. I halted in that narrow, uninviting street, confounded, and the detective left me there.

What could I do? I went up to the Rue Lepic, saw Pierrette’s invalid sister and learned, as I expected, that she had not returned. I told the poor girl nothing of the truth, but left to continue my search.

Throughout that bitter Christmas night I searched alone. But the dawn spread and I could discover no landmark. So I returned myself wearily home, keeping my secret to myself and accounting for the injury to my head by a fall on the slippery pavement.

I searched diligently and well. Through the three years that I remained in Paris I never relaxed in my efforts, yet that maze of dark streets, with their high houses and dingy sun shutters all so closely resembling each other, baffled me. I felt convinced that the house I had entered was not the same one through which I had escaped.

To that dingy room in the Rue Lepic Pierrette never returned. Many were the inquiries regarding her in the quartier. I alone, with a burden of bitterness in my heart, knew the secret of her terrible end.

I left Paris at last. For years I drifted hither and thither across two continents. I forsook the profession for which I had studied, took up literature, struggled hard, and at last became known. The only shadow upon my happiness was the conviction that my duty was to discover those assassins.

But all was useless. The police had long ago refused to believe my story, and time made it always the more difficult to rediscover the scene of the crime.

Many times since my student days have I been in Paris and wandered about Montmartre. Ah! how it has changed since that December morning when I followed the trail of that wooden-legged man through the untrodden snow and so nearly escaped a terrible end. But that was ten years ago and ten years form a good slice from a man’s best days.

The denouement of the strange drama in Montmartre only occurred last July, and a remarkable denouement it proved to be. My own wanderings had taken me back to Paris to pilot some English friends around the exhibition, and having done most of the attractions, from the moving sidewalk to the Algerian dances,8 it was suggested that I should take them to see other “sights.” Rather ungraciously, I believe, I consented to take them for an evening up to my old student haunts in Montmartre and show them the cabarets and “bals-musette,”9 which the ordinary visitor to Paris never sees.

We commenced the cabarets of Bruant, “Les Quatr-z-Arts” and “Le Treteau de Tabarin;” we visited that gruesome undertaker’s shop called the “Cabaret of Death;” spent a quarter of an hour at the tribunal comique at Le Carillon, looked in at the bal-musette in the Rue Coustou, one of the most dangerous but most interesting in Paris, and at midnight took a drink on the terrasse of the “Dead Rat,” before passes the whole panorama of the gaslit gayety of Montmartre.10

Having sat there half an hour, one of my companions—they were three respectable Englishmen—expressed a desire to enter the “Cabaret of Hell.” It was a small place, entrance a grinning demon’s mouth with monster tongue, terrible teeth and glaring green eyes. Painted black and read [sic] and illuminated by red lights, its façade was certainly attractive and in striking contrast to the counter attraction of “Heaven,” next door.

In all my wanderings I had never entered there because of a superstitious horror which I cannot explain. Nevertheless, we went, passing through the demon’s gorge into a dimly lit cavern, the black walls of which were covered with creeping, scaly monsters, where in a great cooking pot three of the devil’s angels were playing guitars, while a devil in Mephistophelian garb handed us to seat at an illuminated table of green glass which rendered our countenances pallid as death.

The Cabaret of Hell (photo by Eugène Atget, “Cabaret de L’Enfer : Bd de Clichy”, ca. 1910-12, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

“Avancez, belles impures!” cried the demon to some ladies. “Assavez vous, charmantes pecheresses, vous serez flambees d’un cote comme de l’autres.”

Presently, at orders from Satan, we passed into a second cavern more gruesome than the first and when all was quiet and the lights lowered the man explained that he was about to show us the tortures in store for sinners.

At the end of the cavern a piece of the wall fell away suddenly, disclosing a scene which caused me to spring from my seat and cry aloud.

In the darkness before me was a woman – a beautiful dark-haired woman in white, clinging rope representing an angel.

In an instant I recognized her. It was my own Pierettte [sic]!

She was standing upon a pile of faggots, chained as a martyr to a stake, and the devil bent to the wood and ignited it.

The flames leaped up around her ere I could rush forward, but my wild progress was barred by a couple of Satanic attendants, the performance was abruptly stopped and my love vanished.

Her face was the same sweet, angelic countenance that it had been ten years before. She had not aged a single hour since that night when I had seen her in the hands of her enemies.

I pressed forward to the man who called himself Satan, called him aside and demanded an interview with her.

Antonin Alexander dans le rôle de Méphisto au Cabaret de l’Enfer (photographer unknown, Wikimedia Commons)

“Ah! Monsieur,” he laughed, “I fear that is quite impossible.”

“Impossible? Why?” I cried.

“Because what you see is only an optical illusion thrown upon a mirror.”

“But she is concealed somewhere here and reflected. I must speak with her at once!”

“Alas! you cannot.”

“I will! She shall tell me everything! I will make her speak!”

“Then Monsieur’s power is greater than mine,” he laughed, “because your love is only a figure of wax!”

“Of wax?” I gasped.

“Come and see,” he said, and conducting me through a passage he showed me my love standing there erect, motionless, with her bare white arms outstretched—a statue in hard, cold, wax!

“From whence did you obtain this?” I demanded quickly.

“I bought it eight years ago from old Jean Poirier, the showman. With his partner, Delport, he was one of the most clever manufacturers of wax figures,” he explained. “This is his masterpiece and is no doubt a cast from life. I paid 700 francs for it. We call it ‘The Beautiful Face.’ But you say you knew the original. Who was she?”

“Tell me first. Did Poirier have a wooden leg?”

“No; but Delport had. Both are dead now. Poirier died a year ago.”

“Where did they live?”

“Both lived just at the back of here, in the Rue Gunnard. They had their workshops on the ground floor. The house had some murder mystery, for when the place was pulled down there was found beneath the cellar a quantity of bones buried in quicklime. Only one thing may lead to the identification of one of the victims—a small gold crucifix and chain which the police have.”

“Tell me,” I asked. “In taking casts of a living person, is there danger of death from suffocation?”

“Of course; great danger. My own belief is that the bones are those of women who died under old Poirier’s hands while taking casts of them,” the man replied, frankly.

That same night I saw, at the Prefecture of Police, the little gold crucifix and recognized it as the one I had given Pierrette.

Then, when I reiterated my story to the police, they agreed that the woman I had loved had been enticed to old Poirier’s by an offer of money and, having been suffocated while the plaster cast was being taken, the pair had buried her secretly.

I had intruded upon them, and to save themselves they had cast me into the flushing chamber of the sewer.

The severed head placed with me in that fatal chamber was, no doubt, an imperfect one of wax—the first taken from the mold. I remember well how hard and white were the lips that a silk handkerchief was wound about the hair, and that the part severed from the trunk was white, like the rest. The eyes, too, were no doubt of glass.

The chain of circumstances was remarkable, but today up on Montmartre dramas of life quite as strange are being enacted year in, year out, without ceasing.

Today any visitor to the “Carabet [sic] de l’Enfer” may see the reflection of my lost love, Pierrette, and today, as I wrote, the tiny gold crucifix, my only present to the pure, honest woman who loved me, hangs upon my watch chain.

Footnotes

-

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 23, 1900, PageA10. Proquest Historical Newspapers. ↩

-

The Rue Cassette is a street in Paris near the Jardin du Luxembourg. It and the surrounding blocks are home to the Catholic Institute of Paris, likely the law school that our narrator and his friends attended. ↩

-

The name Pierrette is the feminine version of the name Pierrot, a character in Moliere’s Don Juan who rapidly became a stock character in theater productions across Europe, from the 17th century through the 20th. Pierrot’s manifestations run the gamut from comedic to tragic to revolutionary, but at their heart is love, often unrequited. Pierrette emerged as a character in her own right in the late 19th century, a supporting character and rival for Pierrot’s affections. Le Queux’s Pierrette seems to return the narrator’s affections, but is there a hint of some reservation in this scene? ↩

-

The black velvet cap is probably the faluche, a style of hat taken up by Parisian students in 1888. The “verveau de Paris” has been a little mangled, but seems to be Le Queux’s attempt at turning verve (eloquence, wit) into an adjective to approximate something like “the learned of Paris,” or maybe “the Paris intelligentsia.” ↩

-

Montmartre is a historic Paris neighborhood known in the late 19th century for its arts communities, cafes, and cabarets. The Boulevard de Clichy, which runs east to west through the neighborhood, is home to the Moulin Rouge. ↩

-

Although Le Queux doesn’t translate it for us as he does the other terms here, Forneau was slang for a beggar or hobo. ↩

-

Both a literary reference and a cabaret, the physical Abbaye de Thélème offered an homage to Rabelais’s anti-abbey, a celebration of free will and decadence. ↩

-

Both of these attractions were features at the Paris Exposition, the 1900 world’s fair. ↩

-

The bals musette were popular music halls that primarily featured accordion music like polkas and waltzes. ↩

-

These are all real cabarets operating in fin de siècle Paris. At the cabarets of Bruant, Aristide Bruant performed a sort of stand-up, lampooning wealthy Parisians who attended his show. <li> Les Quatr-z-Arts are properly the Cabaret des Quat-z-Arts, a multi-medium exhibition space. The “four arts” were architecture, printmaking, painting, and sculpture. Le Treteau de Tabarin was founded in 1895 next door to Le Chat Noir. The Cabaret of Death was actually three cabarets, each with a different theme - heaven, hell, and nothingness. Le Carillon was another artistic cabaret. The idea of the tribunal comique or mock trial might be familiar if you’ve watched Interview with the Vampire. André Warnod’s 1922 Les bals de Paris seconds Le Queux’s description of the Rue Coustou bal as having a réputation déplorable et méritée. The Dead Rat was the unfortunate nickname of Café Pigalle. ↩